![]()

|

|

|

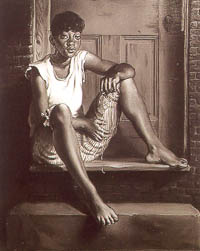

1. Back Porches, 1956

2. The Block, 1954

3. The Kiss, 1959 4.

Girl in a Slip, 1953 |

|

|

Jacques

Maroger |

|

|

Mrs.

John Work Garrett |

|

|

R.P.

Harriss |

|

|

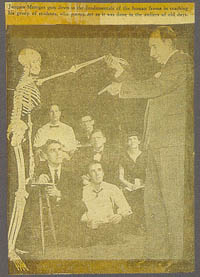

The Maroger

Group |

|

|

Girl

With String, 1953 |

|

|

The Garrett

Mansion, |

|

|

Two Artists

in their Studio, 1952 |

|

|

Jacques

Maroger in his studio on the Garrett Estate |

|

|

Detail

of Painting by John Bannon of Maroger's studio |

|

|

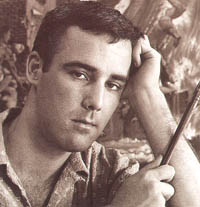

Joseph

Sheppard, 1955 |

From 1940 until 1954 Maroger commuted to Baltimore from New York, teaching classes a few days a week. Only in 1954, two years after Mrs. Garrett died, did Maroger relocate to Baltimore and move into the studio that Mrs. Garrett had built on her estate. For many years, Mrs. Garrett had been saying to Maroger that if anything happened to her, the studio could be his. Although Mrs. Garrett left nothing in writing, the members of the board of the Evergreen House Foundation which she established very enthusiastically gave the studio to Maroger for his use as a studio and as a place to live until his death in 1962.' Introducing Maroger to Hans Schuler, Sr. and helping him secure a teaching position is just one example of the kind of generous, multi-dimensional patronage Mrs. Garrett bestowed on contemporary artists whose work she believed in and supported. Artists loved Mrs. Garrett's patronage for she developed lasting friendships with many of the artists from whom she purchased art. But what artists really appreciated about Mrs. Garrett was the very serious attention she gave to her own painting. Mrs. Garrett even took classes at The Maryland Institute from Maroger himself, painting along side his young students.

When Jacques Maroger arrived in Baltimore to join the faculty of The Maryland Institute of Art, he was 56 years old and an accomplished painter, teacher and restorer. Maroger always said that his familiarity with the old masters' techniques was what made him a good teacher and restorer. This familiarity came from his training as a painter. Maroger studied first with the French portrait painter Jacques Emile Blanche, who later sent Maroger to study with his friend and fellow countryman, artist Louis Anquetin(1861-1932). Anquetin had himself been a friend of Van Gogh, Toulouse-Lautrec, Degas and Renoir. After a brief flirtation with Impressionism, Anquetin returned to the study of the old masters, Rubens, Hals and Rembrandt, trying to rediscover their lost painting techniques. Following Anquetin's guidance, Maroger copied paintings of the old masters and studied anatomy in a dissection class of a medical school as he took up and continued his teachers research into the colors of the old masters' pigments and the brightness, transparency and permanence of their canvases. Maroger was to continue this research throughout his life.

In 1929, while at the Louvre, Maroger was credited with discovering the first oil painting medium of the 15th century artist Jan Van Eyck. This initial discovery was published by the British Academy of Science in 1931, arousing the interest of the critic Roger Fry who invited Maroger to give a painting demonstration. A number of English artists, among them Augustus John, then became enthusiastic users of this new medium. In 1937, when Raoul Dufy was commissioned to paint a 36 by 220 foot painting of L'Histoire de I'Electricite for the Paris World Fair, he used the Maroger medium, choosing his friend Jacques Maroger as his technical adviser. Later that year, Maroger was awarded the Legion of Honor for his contribution.

Maroger was best known for his rediscovery of the mediums of Jan Van Eyck and other Flemish and Italian Renaissance painters long before his research was published in 1948 in his book The Secret Formulas and Techniques of the Masters. But his strong feelings about the proper training of young artists was also becotaing equally well-known in Baltimore. Maroger emphasized the technical foundations of painting in his courses. Just as he had been urged to study anatomy and return to the museums to copy the work of the old masters, so he required that course of study for his new students at The Maryland Institute. Maroger also insisted that his students prepare their own medium, which they did by combining and cooking oils, lead oxide and other substances according to formula. Maroger further insisted that his students grind pure colors for mixing with the medium. Only with these materials could they begin to reproduce the colors and luminosity of the old masters.

As Maroger began giving his Institute students an intensive training in anatomy, drawing, sculpture, portraiture and still life painting, combined with instruction in how to grind pigments, hand-press linseed oil and make media, he also began dreaming about the development of an American school of painting, grounded in that knowledge. The first to join Maroger as a post-graduate student and as an assistant was Ann Didusch Schuler, who remained his teaching assistant throughout his 19 year tenure at The Maryland Institute. Then, beginning in 1946, just after the war, a number of students arrived at The Institute and joined the Maroger group, including Frank Redelius, Earl Hofmann, Evan Keehn, Thomas Rowe and John Bannon. Many other students followed, including Joseph Sheppard. Melvin Miller was among the very last of Marogers students often referred to as his disciples.

When Joseph Sheppard entered The Maryland Institute, he was painting abstractly like most of his fellow students. He was not a member of the Maroger group, initially, but he was living with one, Earl Hofmann, who kept encouraging Sheppard to come and paint with them. One day, during his second year at the Institute, Sheppard took Hofmann up on his offer and went to the Maroger studio to paint. When Sheppard completed his painting of an interior space with two figures, Maroger came over to see it. Maroger was delighted and said to him, "Paint three more like that, my boy, and I will get you into a New York gallery!" Sheppard studied his remaining two years with Maroger and never painted abstractly again. Mr. Douglas Gordon, a well known civic leader in Baltimore, bought the canvas Sheppard had painted in Maroger's studio that day and remained a good friend and patron. Sheppard painted many more canvases like the one Douglas Gordon purchased and Maroger got him into the Grand Central Gallery in New York, along with many of his Baltimore students.2 Sheppard became an ardent disciple of Maroger's and enthusiastically embraced the return to the principles of classical art and the use of the human figure in his work. He also embraced Maroger's teaching of the importance of drawing and became an outstanding draftsman. During the years Sheppard was at the Institute, many established artists came to Baltimore to learn about the Maroger medium directly from Maroger. One such artist was Reginald Marsh, one of America's great genre painters, who came down from New York every summer for more than ten years until his death in 1954.

On at least one such visit to Baltimore, Marsh was a guest of Mrs. Garrett's at Evergreen House and in his now famous letter to her, he congratulated her on her intense application to her own painting and "to the great aid given to a movement which is sound, but not a la mode". He ended his letter by saying, "This new medium of Maroger's is certainly the greatest gift to the technique of oil painting. I'm going to stick with it."5 Marsh had a very strong influence on Sheppard and the other young Maroger students with whom he painted each summer.

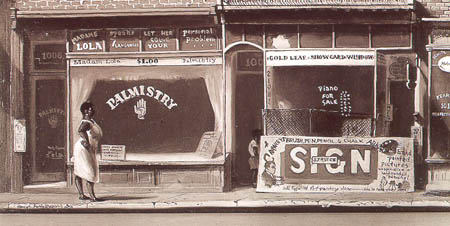

Marsh's social realism lead Sheppard to realize the value of combining the human figure within scenes of Baltimore's urban life, for which he became so well known soon thereafter. Sheppard's earliest subject matter included life in the black ghettos and the strip joints along Baltimore's famous Block. Marsh exhibited enthusiastically with these young Maroger disciples and Ann Schuler and Maroger at the Grand Central Gallery in New York and at the Mt. Vernon Club in Baltimore.

Palmistry, 1953 Chiromanzia (Prize "Life

in Baltimore" Peale Museum 1953)

These exhibitions were all arranged by Maroger in his effort to influence the direction of contemporary painting away from abstraction and back to a classical realism, toward what he hoped would be the new school of painting. Sheppard's career was moving forward. In 1957, just five years after finishing his studies with Maroger at the Institute, he won a Guggenheim Fellowship and spent the next year in Europe, mostly in Paris and Italy. By 1958 he had had one man exhibitions in Paris, Washington, Boston, Philadelphia and New York. As Sheppard's career was advancing, his mentor's was winding down. Maroger left The Maryland Institute in 1959, after a number of new presidents began steering the school away from the academic tradition. Abstract expressionism had taken a firm hold. Maroger withdrew to his studio at Evergreen House to continue his research and writing and to paint. Maroger became an advisor to Ann Didusch Schuler who left The Maryland Institute at the same time and with her husband Hans Schuler, Jr. opened the Schuler School of Fine Arts later that year. Ann Schuler was committed to continuing Maroger's teaching methods.

By 1961, Sheppard and the other early students of Maroger were making

headlines in Baltimore and the idea of an American school of painting about

which Maroger had dreamed for so long seemed to be given new life. A controversy

arose after it became known that Baltimore's realists

painters were not

among those artists chosen for that year's Maryland Annual Exhibition at

the Baltimore Museum of Art. The dispute erupted in the newspapers, covered

primarily by the well known News American art critic R.P Harris, who asserted

that Baltimore had one of the largest and most dynamic communities of representational

painting in the country but one would never know it from the regional exhibit.

The artists accused the BMA of following a pattern of fashion set down by

museums in New York and Paris and of becoming an exclusive private club

from which contemporary realists were virtually banned. In response to this

situation, the realist painters organized a kind of "Salon d'refuse". With

Joseph Sheppard and John Bannon in the lead, Frank Redelius, Earl Hofmann,

Thomas Rowe and Evan Keehn, all early students of Maroger, opened the salon

at 817 N. Charles Street on the same night the BMA opened its annual regional

show. Two thousand people attended the opening at what was being called

the Six Realists Gallery. The headlines the next day read, "A triumph in

every way." R.P. Harris wrote a strong review, stating "Whether this group

will form the nucleus of a recognized school dedicated to bucking the non-objective

craze remains to be seen. As of now, they are a credit to their patron,

St. Maroger."4 Instead of a three week exhibition of realist paintings by

these disciples of Maroger, the gallery remained open and strongly supported

for three years. The group of six realists changed over the years and included,

in addition to the six founders, Melvin Miller and David Walsh.

In the middle of this resurgence of realism, on June 28, 1962, Maroger died at Evergreen. By the end of the next year, the Six Realists Gallery had closed after its third season, and the artists scattered to pursue their own diverging interests. But before it closed, Sheppard and Bannon and the other Maroger followers had succeeded in putting Baltimore on the map as Maroger had hoped and several had achieved even wider acclaim. Often paintings by the Six Realists were juried into the annual exhibitions at The Butler Institute of American Art in Youngstown, Ohio. Most notable was the inclusion of work by Sheppard, Rowe and Miller in the 1962 Annual at The Butler Institute, along with work of Ben Shahn and Edward Hopper. Sheppard's painting, Mr. Mack's Fighters' Gym , won first prize in that show. It was a purchase award and the painting became part of The Butlers permanent collection. The assistant director at The Butler described Sheppard "as one of the most gifted artists in America today".5 The Butler continued to exhibit Sheppard's work. One later exhibition, entitled Artists at Ringside included work by Sheppard, George Bellows and Thomas Eakins. Eight of Sheppard's paintings were shown in that exhibition, including his now famous Descent from the Ring.

From his earliest days as an artist, Sheppard had great success in his hometown of Baltimore, in New York and elsewhere, in spite of the fact that the movement he was part of was, as Reginald Marsh had said, "not a la mode". Sheppard earned an enviable reputation as a realist painter in various guises and genres, as a painter of street scenes, barrooms, fighters and strippers- all life around him. Sheppard has always been a remarkable Baltimore Realist - one whose rare talent Maroger and many, many others recognized immediately. Sheppard's earliest paintings, beginning with the work he did at The Maryland Institute and throughout the 1950s, will be exhibited in Baltimore at Evergreen House when the newest work from this current exhibition will be on exhibit at The Walters Museum-a very appropriate way to celebrate fifty years of painting.

Cindy Kelly

Director of Historic Houses

at John Hopkins University